Downmapping

Downmapping is the process of taking your initial difficulty, breaking it down into its core ideas and motifs, and then translating those ideas as appropriate for other respective skill levels.

While the process of downmapping may look daunting to the average mapper as opposed to releasing just a single difficulty, there are a variety of benefits that draw many to the process.

- Having multiple difficulties can make your map more enticing for a greater audience of players, regardless of their skill level and experience with the game.

- A solid difficulty curve keeps players coming back to your maps over and over again as they improve, and allows you to build a reputation among all levels of players that will stick with them for all your future maps.

- The process can also reinforce fundamental mapping skills with greater consideration for musical representation, body mechanics, and accessibility to the wider playerbase.

While some mappers may not be concerned with big download numbers or cultivating a larger playerbase, downmapping is still something to consider at any point in a mapper's journey.

There are no finite rules when it comes to downmapping, as there is no correct way to create a spread of difficulties. In fact, most mappers can neglect some of these guidelines and still manage to make a quality spread of difficulties. Instead, we will provide a robust series of guidelines on how to spice up your lower difficulties, with explanations for why downmappers have come to adopt these insights as well as other tips that can help you make engaging lower difficulties that anyone, regardless of skill level or experience, can enjoy.

For a more simplified explanation on the basics of downmapping, you can check out in Basic Mapping: Gauging Difficulty & Down-Mapping.

Know Your Demographic

Truthfully, the guidelines you will want to incorporate when building lower difficulties will depend on the demographic of players you tailor your map for. Most mappers will rely on methodologies that are directed towards accessibility, modeled after a community interpretation of conventional mapping practices from the base game. While some of these guidelines may not be adopted by the official mapping team verbatim, they were formed from observations of various players, watching as they play through a wide range of lower difficulties and taking into account their natural tendencies for a wide range of patterns.

When creating lower difficulties, the goal of a mapper is to work within the expectations of your target audience of players at a respective difficulty level, while gradually introducing new concepts and mechanics of the game to provide a fair challenge. The goal of a player is to learn the various facets of the game at a comfortable pace without being subjected to too many complexities at once. When a mapper expects too much out of a lower-difficulty player, the player may be too overwhelmed in their limited experience with the game and ultimately fail out of the difficulty. By limiting the scope of what you expect out of a lower-difficulty player, you allow the player to learn at their own pace, which can make the map less punishing when they fail to grasp the necessary skills and more rewarding when they do.

The key to downmapping lies in having a solid understanding of what is fun and playable for a typical lower-difficulty player. However, another important aspect to consider is how well you've represented the music within your mapping. It's easy to throw together a map that an inexperienced player can pass, but the magic of your initial difficulty can be lost if you fail to translate those same concepts and ideas. You should know what the “key” moments in your map are and try to highlight them across all the difficulties. This may require creating similar patterns that fit a wider skill range, but this approach is necessary to help keep life within your map.

TIP

The common interpretation of the five difficulty labels may create issues for some spreads. It's perfectly acceptable to have a difficulty in a spread that is more difficult than what would be expected at that level, but you should consider pushing your labels up using custom difficulty labels if this is the case. A player that finds an Expert+ difficulty when they are expecting to play a Hard level is not going to have a fun time.

Rhythm Choice

The most common aspect of downmapping that most mappers initially tend to struggle with is how to properly gauge the reduction of rhythms across the spread. The NPS value of a difficulty can be used as a frame of reference, but the overall difficulty of a level should be more heavily influenced by pattern choice rather than rhythm choice. As a general baseline, you should aim to reduce the overall note density of each difficulty by approximately 20% as you work your way down the spread, but this range is not absolute and will vary depending on the feel of the song.

For more information on the NPS ranges across all maps within the base game, check out the Beat Saber Map Analysis tracker.

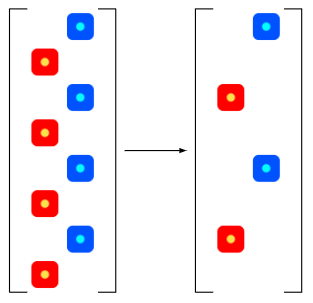

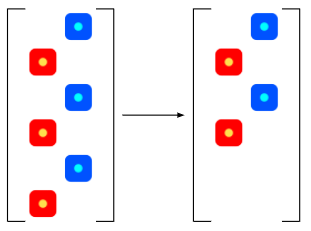

Density Reduction

For any series of dense patterns at high precision values (such as streams or jumps), you should simplify their usage or reduce their precision within reasonable expectations for players at their respective skill levels.

- For Expert, you should simplify sustained usage of 1/8 and 1/6 timings from your Expert+ difficulty.

- For Hard, simplify usage of 1/4 from Expert.

- For Normal, simplify usage of 1/2 from Hard.

- For Easy, simplify additional usage of 1/2 and/or 1/1 from Normal.

The common methods of simplifying rhythms include, but are not limited to, the following approaches:

- Cut the precision of a section of notes in half.

- Add small breaks between denser sections of notes within a measure.

- Consolidate usage of note placements at higher precisions into more emphasized variations at lower precisions.

Musically Founded

While it's wise to stick within conventional NPS ranges to start, as long as your levels have a clear progression of difficulty they don't need to fit neatly into a box. In fact, a variety of base game maps have large fluctuations with NPS ranges (for example, "Father of All..." from the Green Day Music Pack flaunts a one-note difference between the Expert and Expert+ difficulties). This is by design, as the foundations of rhythm choice for lower difficulties correlate with a basic understanding of music theory.

- You will find Expert+ to be the all-encompassing difficulty, providing a more robust syncopation of rhythms as the mapper aims to emphasize every sound and flourish they deem appropriate.

- Expert is interpreted as the basic understanding of the song's structure, so if the mapper chooses not to retain the same rhythm choices established in Expert+, you may instead find the difficulty anchored to a sole musical structure or instrument within the composition, such as the percussion or melody.

- Hard and below is where simplicity starts to play a more imperative role than musicality, so a more structural rhythm choice may be established, one that would compliment the expectations of note density for the respective difficulty level.

TIP

As most mappers tend to start with Expert+ or Expert, the process is usually referred to as "downmapping", since you work your way down through the difficulties. However, some mappers can and do work in the reverse, or even just map difficulties sporadically as they see fit. That said, starting from the top gives you the benefit of saving time on timings, as Expert+ will typically encompass all of the song's most prominent rhythms and syncopations.

Pattern Choice

Hard & Expert

Hard is where Beat Saber as a game truly begins. Players with any sort of background in VR, or even video games as a whole, will likely start at this difficulty or very quickly graduate to it within a matter of hours. Core mapping principles become very important in Hard, although the slower speed (compared to Expert and above) can make some patterns less egregious. Flow, in particular, should become standard, and every swing should obey parity, although Hard players will still reset when given enough time and space to do so.

Hard players will have a solid understanding of the mechanics of the game, including how the scoring system is operated. Players in this range are starting to be introduced to different styles of mapping, and may begin to prefer certain styles or gravitate towards competitive play. It's important to make sure your Hard difficulty has some sort of identity and properly represents the music. Consider your Hard difficulty to be the entry point for your specific mapping style.

Your Expert difficulty should continue to grow and expand upon the style introduced in Hard. An Expert player can typically handle most patterns at a confident level; they can read simple patterns, keep up with higher precision for longer periods, and can generally play the game at a higher level. However, it is a trade-off. Complicated syncopations or dramatic spikes in complexity can easily overwhelm an Expert player.

Remember

Sight-reading is a skill that is still being developed for most Expert players, and you should make sure you're giving the player enough time to react to whatever you throw at them.

Spacing & Complexity

For Expert, most of the patterns should be similar to your Expert+ counterparts, but follow a more simplistic form that is easier for a player to interpret. Do not be afraid to oversimplify a pattern if it ends up being too complex than what would be expected out of your target audience.

- For patterns that involve a higher density of notes involving more rapid swings (streams), it's better to direct the player's focus on timing rather than readability. You should try to compact the swinging paths of the notes to less demanding positions, and always maintain a clear line of sight for all notes within the section. When sustained over a long period of time, try to incorporate breaks so that the player can recover if they end up losing track of the flow.

- For patterns that involve a more pronounced reach of the player (jumps or inverts), establish a clear reduction in the spacing between the notes. Stamina is a big contributing factor to the limitations of this group of players, and players at this level are still trying to maintain full control of their swings. Reducing the spacing between notes or incorporating proper breaks can help make these sections more forgiving.

For Hard, the style should follow the same simplicity-driven approach used in Expert, and reductions in spacing and complexity should be more noticeable in comparison.

In addition, Hard is generally the skill level where the concept of parity will be reinforced, but not yet mastered, by the player. While players may be working to maintain flow at this difficulty level, there may be instances where natural tendencies may prompt a player to reset when patterns are getting too dense or too complex. For sections with enough spacing after a pattern, for patterns that resolve to opposite parity on each hand (scissors or side doubles), or even for the purposes of representation, you may find that using a reset to reorient the player may be more effective than maintaining proper parity.

Crossovers

A majority of players at the mid-difficulty levels may not be able to properly read or play crossovers at this level, as they typically lack the full commitment to reach towards the opposite lane and follow through on their swings. When building a lower difficulty in a style that caters to more wrist-favored playstyles, certain setups can be dangerous if the patterns are not immediately obvious to the player on how to swing for them.

Do not expect a player at this level to be able to maneuver their hands behind each other to unwind themselves out of crossovers, and be wary of creating unintentional arm tangles with more lax setups. If you decide to use full-body crossovers, they should be isolated hits with plenty of room for setup and recovery, and make sure that you properly unwind the player's hands and lead them back into a more comfortable position.

Easy & Normal

Easy is, essentially, the "New to VR Difficulty". Players that can only pass Easy maps likely have zero experience with video games or VR. It is very easy to take for granted how much innate knowledge you might have from growing up in a digital age. VR is extremely overwhelming for someone that has never experienced anything even remotely similar to it, and your map might be the first VR experience the player ever has! Keeping that in mind, it's important to keep your Easy difficulty as simple as you can. Easy players are soaking in the experience and are learning the most basic of fundamentals, including which arm is which, and even how to orient themselves within a virtual world.

From there, players will eventually work their way up to the Normal difficulty. You can expect the Normal player to be less distracted and have a larger grasp of Beat Saber's core premise as a game. They are more likely to understand obstacles and read notes as opposed to just swinging for them. That said, they still need a good amount of time to properly react and recover, especially at any memorable moments in a map, and they will still try to reset at any given opportunity. Big, flashy movements with a lot of time before and after are a great way to win a normal player's heart.

Breaking Parity

I already know what you're thinking. Why build a lower difficulty around a design philosophy which abandons the very concept that is required to progress to the higher difficulties? It seems counterintuitive, but this approach proves to be more effective when you take into consideration the general limitations of players at this level of skill.

Remember, Easy and Normal players will generally be inexperienced to Beat Saber, to VR, and possibly to rhythm games in general. With this lack of experience, they will likely neglect to grasp the nuances of higher-level mechanics and concepts, such as the very nature of “flow” that more experienced players will have a greater understanding of. By this expectation, it may be better to anchor the mapping style to play into those natural tendencies and build the difficulty around their limited experience with the game.

Some mappers may likely neglect to see the appeal for this process, as the approach ultimately goes against the fundamental nature of the game's mechanics that would be required to advance to the higher levels of difficulty. From a design perspective, this relies on two primary reasons:

Limiting Factors. These will be described in more detail below, but refer to the indirect “rules” for pattern creation that you should account for when making accessible lower difficulties. Grounding the mapping style to a perfect flow state as you would typically do in the upper difficulties may limit the potential in how you can build a lower difficulty, especially when limiting factors and rhythm choice already impose enough restrictions on their own. By using parity breaks as a tool for representation, you will have more options to preserve the map's identity across the spread and make each difficulty feel more like a “progression” of the same core ideas. For some, this proves to be more beneficial for reception than trying to impress a concept that a new player may not be able to easily grasp.

Player Freedom and Leniency. The goal of using parity breaks in lower difficulties is not necessarily to break the fundamental flow of a map, but instead aiming to establish a neutral, or ambiguous, flow. The mapper is not necessarily trying to force the player to swing for patterns in any particular way, but rather allow the player to swing in whatever way feels more natural to them. This approach allows for more flexibility in the map's design for how a player can “correctly” play through the map, while also making patterns more forgiving in the event the player misinterprets the intended flow.

With these considerations in mind, don't be afraid to break parity. Like, a lot. In fact, typical Easy difficulties will almost be entirely composed of parity breaks with very little notions of proper flow.

For Normal, resets are still advised for the expectations of players at this level, but you can start to introduce the notions of flow in a more isolated series of patterns that would be deemed too quick for a proper reset.

Limiting Factors

While dismissing the concept of parity can provide more freedom in how you could conceptualize patterns for Easy and Normal difficulties, there are still a series of indirect "rules" that you should be taking into consideration if your goal is to make your lower difficulties more accessible to typical lower difficulty players.

Remember, these players are still generally developing the fundamental skills of the game, such as timing, basic readability (red on left, blue on right), and/or mobility, so you should always keep these considerations in mind when building these difficulties.

TIP

At the lower difficulty levels, there are plenty of ways to create unique syncopations without using a consistent left-right alternation of up and down swings for the entirety of the map. You have plenty of patterns at your disposal that can help maintain the musicality of your difficulty, including side notes, doubles, and even utilization of the middle row. This variety is what ultimately keeps the player engaged throughout a lower difficulty and can help make up its identity beyond the rhythm choices alone.

Diagonals

Mappers will typically claim that diagonals are not recommended at these difficulty levels, as cardinal directions will almost always be easier to parse for newer players than diagonals. However, diagonals are acceptable to use with extreme consideration into their use cases. These hits should be extremely simple for a player to parse (they should be no more difficult to understand than if they were cardinal directions), and should not be overused to the point of introducing too much directional complexity at one time.

Top Row Notes & Dots

Some players may be restricted to a limited range of motion, as you will typically find most children and elderly players settling into this difficulty level. As a result, you will not find an overabundance of top-row notes in the lower difficulties, possibly even avoiding them altogether. In cases where top-row notes are used, they are restricted to dot notes and are more commonly kept to the center two lanes.

In general, players will typically swing for any dot note as a forehand hit, with the nature of dot notes being introduced as a swing in any direction and forehanded swings to be more comfortable for a player's natural tendencies. This is especially the case since the in-game tutorial encourages the player to interpret dot notes as “hits in any direction” as opposed to “upward hits”.

Side Hits

Side hits can serve as a great tool for emphasis and representation, especially when these difficulties rely so heavily on a large reduction in note density, and the only way to create that necessary emphasis would otherwise be with doubles. In most cases, side hits are going to be played with a more ambiguous flow depending on how the note is positioned on the grid, and players will tend to play side notes in whatever fashion is more comfortable for them.

For Easy, the common expectation is that all side hits should be primarily played as forehanded hits, but it's always wise to account for every possibility in how a side hit could be interpreted.

For Normal, you can expect a similar case to Easy. In some scenarios when notes are too close together for a proper reset, you can resolve a side hit to typical flow, but you should always assume that the player will play side hits unintentionally to the mapper's original vision.

Stacks, Sliders, & Variations

For Easy, you may want to avoid using stacks and sliders altogether. These hits will always require greater confidence of a player to follow through on their swing (most players are typically going to be fencing with their level of skill and confidence in their abilities), and there are better ways to create emphasis without adding unnecessary visual clutter.

While not typically common for this difficulty level, you could start to introduce stacks and at most two-long sliders at Normal. However, they should be used both in moderation and depending on the context of representation, with plenty of time to parse and setups that remove all ambiguity in how to hit them.

Any other general variation of these over-emphasized hits, such as towers, windows, and three-long sliders, will likely be too ambitious for this level.

Scissors and Inverted Doubles

For Easy, any pattern that involves parity to be interpreted independently of each hand will not be something you should expect a player at this level to be proficient with, as these players will more often than not syncopate the movement of both hands with similar parity when approaching any configuration of a double.

For Normal, you may start to introduce the concept of scissor-like patterns, but they should be treated as a more complex pattern. These hits should be extremely easy to parse and recover from, with plenty of spacing between successive hits (you will typically not see more than 3 or 4 used in a consecutive sequence).

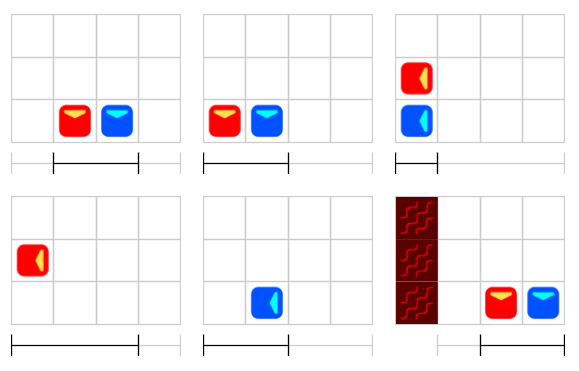

Crossovers

Crossovers of any context are not expected of players at this level. In fact, most players will refuse to leave their hands in a crossover position, and will instead shift the movement of both hands within the same relative positions to each other.

This characteristic is something you will commonly see in any rhythm game, where natural tendencies will cause a player to consistently return to a more centralized position. As a result, you can use far lane notes and/or walls to cue the player into shifting their centralized position to the left or right and allow for more comfortable note placements at the far lanes.

However, be wary about how you orient the player's hand positions when drifting into the outside lanes. In most cases, you will never see a red/left note drift to lane four or similarly a blue/right note drift to lane one.

Locomotion Walls

For walls that introduce any form of mobility, such as dodge walls or crouch walls, make sure the player has plenty of time to prepare themselves as a wall approaches them, and give just as much time and spacing to return to a central, standing position. Try to remove any ambiguity in how the player is supposed to react to a wall, such as marking dodge walls with the full two-lane widths and crouch walls with four.

In addition, it may be ill-advised to incorporate any dodge or crouch walls that are directly syncopated with notes at these difficulty levels, as players will find enough difficulty dodging an obstacle on its own than having to factor in a swing syncopated with physical movement.

NJS & Offset

The NJS of your map will affect both the spacing between notes and the timing windows provided for the player. A larger value will make your map more readable at the cost of being more timing-dependent for the player. The best way to determine the ideal NJS value for your map is to aim for the lowest possible value that would ensure a balance between the readability and playability of your map. Make sure the NJS value you choose can provide a clear line of sight for notes in the densest sections of your map, while also giving the player a fair and lenient timing window to comfortably and accurately swing for.

For Expert+, the maximum NJS that has been used in an official capacity within the base game is 23, so you shouldn't need to go higher than this in most cases.

For Easy and Normal, you will typically find the NJS to be anchored to 10 to make the transition into customs as smooth and familiar as possible for players coming off of the base game maps. Some mappers like to bump the NJS slightly higher or lower for these difficulties for personal preference or even better readability in some cases. This is acceptable, but be wary about putting the NJS too high where the map would be too fast for typical expectations. In most cases, 12 would be an acceptable upper limit for these difficulty levels.

For Hard and Expert, the NJS will vary depending on what values are established at the higher and lower end of the spread. Some mappers have found it effective to find values that would create a linear curve of values between the highest and lowest ends of the difficulty spread, but you should always be aiming for the lowest possible value where applicable.

For more information on the NJS ranges across all maps within the base game, check out the Beat Saber Map Analysis tracker.

NOTE

For Hard, the typical NJS per OST conventions is locked to 10, but for the standards of community maps this may not provide enough spacing between notes for readability purposes.

While an ideal NJS value can be properly assessed by a mapper, the Offset of the difficulty is where you will typically find the most variance, as a variety of subjective factors will influence the most suitable value for the map. Even within the scope of base game maps, the typical values for Offset and JD evolve with each subsequent pack release, as each official mapper seems to establish a unique series of preferences for a spread.

A good anchoring point to determine the most viable offset value would be to aim for a Jump Distance within the range of 24-30 for any difficulty within a spread, settling on the higher end of this range for lower intensity maps and vice versa. A larger value will provide more space for a player to parse your patterns, but may create visual clutter with notes at higher precisions. A smaller Jump Distance will provide fewer notes to parse at one time but will require a quicker reaction time out of the player. Ideally, you would want the Jump Distance values for each difficulty to decrease as you work your way down the spread, but this may not be practical for some spreads.

If you prefer a more semantic interpretation of what would be considered appropriate, you can instead ground the offset based on the number of unique patterns within an HJD interval of the difficulty. We will define a unique pattern as any series of notes that lie on a specific point of time, regardless of what type of pattern they make up.

- For Easy, try to aim for no more than 2-3 unique patterns within an HJD interval.

- For Normal, try to aim for no more than 4-5 unique patterns within an HJD interval.

- For Hard and above, this attribute does not play a necessary role.

TIP

Some players will tend to utilize the base game offset modifier to nudge the offset of a difficulty closer or farther based on their own playstyle preferences. As a mapper, it may be wise to anchor the Jump Distance on a value within the recommended range and give players the sole authority to find a suitable offset value, rather than forcing the preferences of the mapper onto them.

- If you typically prefer a Jump Distance lower than 24, your offset value should allow you to comfortably play your difficulty with the Closer offset modifier (

-0.25). - If you typically prefer a Jump Distance higher than 30, your offset value should allow you to comfortably play your difficulty with the Farther offset modifier (

+0.25).

Conclusion

Do not expect to become a perfect full spread mapper overnight. These guidelines are elementary compared to a variety of other considerations that go into a well-made spread of difficulties, and there will always be new considerations that people will choose to adopt and reject based on how the meta will evolve in the years to come. Many of the adopted guidelines mentioned in this guide came from a variety of mappers who have played an abundance of lower difficulties, figured out what aspects of a lower difficulty resonated with them and with players, and through trial and error adapted those ideas into a mentality and workflow to apply to a suite of difficulty spreads.

The primary way to improve your skills beyond that point is to keep making lower difficulties; as tricky as it is to develop a separate mindset for mapping lower difficulties, it will start to become second nature as you start to refine the workflow, and the reception will speak for itself. All it takes is the motivation to hone your skills in downmapping, the research to make it happen, and the drive to see it through until the end.

Credits

Content in this section was authored by officialMECH, with additional contributions from Pyrowarfare, Skyler Wallace, monstor, and other contributors.